Blog

Mythic Impressions

By Jonathan Duerbeck, weekend naturalist

Have you ever seen one animal make different kinds of tracks?

Mud, rock, and snow can all be stepped on by the same raccoon. On each of these, his paw print is different. Likewise, woods, gardens, and seas are each warmed by the same sunshine. That sun draw out different things from each place—branching trees, sprouting radishes, towering clouds.

The natural world is like a raccoon foot reaching through our senses. It leaves varied impressions in the world behind our gazing eyes. And we are all poised to deliver different reactions to our world, out of what’s already inside us.

One summer I led a homeschool group to a creek. Two little girls spied a fat, scaly water snake. One girl stomped her foot, crossed her arms, and demanded to be taken home. The other pulled on my leg and begged me to take her across the water to pet the snake. Opposite impressions from one snake. Those girls had two different kinds of cognitive surface inside them, where the sight of a slithery snake left a radically different emotional track and drew out a different reaction.

A 10-year old boy named Ernesto once said, “I always eat the food I don’t like. It’s really good.” I try to be more like Ernesto, and less like an emotional vending machine. I’ve learned to enjoy cold, wet days, black licorice, and formerly “difficult” people. In every case, seeing or thinking in a new way helped wash away my old, limited impressions.

People who think differently than me often show me new ways to be impressed—especially people from other cultures or times. Some of the most mind-opening new views have come from folklore and myths—the stories passed down through generations to express the meaning that people found in their world.

Consider the ancient Egyptian story of the goddess Isis and the god Osiris. In some versions, Osiris’ brother, Set, tricks the unwary god into lying in a coffin that was made to fit him perfectly. It’s a trap. Set seals the coffin shut and floats it down the Nile River to the sea. Isis finally finds her beloved’s coffin near the shore, swallowed inside the growth of a fat tree trunk. She cuts open the wood to free Osiris, and revives him enough to later bear his child, Horus. In some versions, Horus is Osiris reborn.

I was reminded of that story when I lit a campfire last fall. I saw the sun’s energy as Osiris (sometimes called a sun god). The green leaves trick him and trap him, like leafy spiderwebs whose spiders are green molecules with “mouths” perfectly shaped for swallowing quanta of light. The plants then float the trapped sun-power down the rivers of their veins to be hidden inside their wood. Thus, every leaf and stick is the coffin of past summer sunshine. And so the plant-covered, algae-filled earth has grown a sophisticated method to receive useful impressions of sunlight.

As the flames rose, I imagined all those chemical bonds of cellulose snapping like prison bars built from light. This fire was the freed sunlight of past summers. Even without fire, Mother Earth brings new life from the bodies of plants—with rot, or the bellies of herbivores. That’s the story of the food chain, bringing the trapped sun energy to life again as a fungus, a deer, or a new plant in soil freshly fertilized by wood ash.

That story helps me feel a deeper impression from the grand movement that bears the unglamorous name of “food web.”

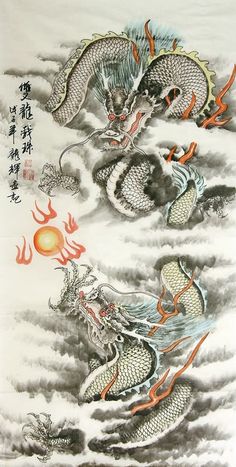

A grand movement of water is expressed in dragon images. In the I Ching and other ancient Chinese writings, dragons are a symbol of the power of the sky, the power to start movement and push out. But the weather-dragons leave the sky to swell the rivers and seas. And like Osiris getting in his coffin, in fall they slip down into the water and earth, where they sleep all winter. When spring comes, they rise up with the earth’s heat in swirling motions to be part of the first spring storms, belching cloud mist and booming out thunder.

The diving, rising dragons are a poetic image of how the earth takes in life from the fiery sun and stores it all winter, to be freed again in spring. At the height of summer, the lengthening days start to shrink, much like a towering thundercloud collapses on itself, to be slain by the cold, condensing knives of its own raindrops, finally bleeding back into the ground like a reversing dragon. Right now, in Fall, life is pulled into the earth, concentrated into seeds, dormant wood, sleeping buds, burrowing animals, buried eggs, roots, and bulbs. That life rests like a held breath all winter, then is exhaled in a flush of sprouting, opening flora and a riot of births and awakenings, until the air is again filled with moving life.

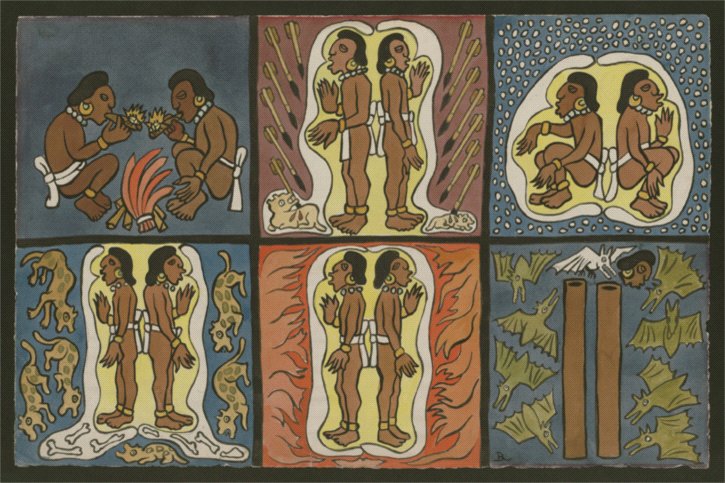

Ancient Greeks described fall as a goddess pulled down to the underworld, and some compared winter to a human lifetime. The Mayan fall story is of twin brothers who journey to the underworld, defeat the gods there, and escape like a sprouting kernel of corn. Many of these underground journey stories showed how people understood their lives. It seems to me that, in their impressions of the seasons, people saw stories about themselves.

Here’s what I see:

Winter deep meets summer tall

In rising spring and dying Fall.

Summer’s light, the Fall will save

To pour it in a Winter grave.

From Winter’s body, Spring will birth

Ascent to Summer sky from earth.

Summer, Winter, Life and Death,

Linked by living Fall-Spring breath.

When we find meaning in nature, or feel solace, or disgust, the world’s footprints show us something about the terrain inside us. What images does fall bring up in your mind? What kind of surface do you have, that lets nature impress you as it does? What story does your experience of nature tell you about you?

You can learn more about the stories in nature on Saturday, October 22, at a program called Legends and Folklore of Fall. For more information visit: http://bit.ly/LFofFall

###

Baynes, Cary F. and Richard Wilhelm. I Ching: Or, Book of Changes. 3rd ed. Bollingen Series XIX (Princeton NJ) Princeton University Press, 1967, 1st ed. 1950. Web: pantherwebworks.com (2015).

Brennan, Martin. The Hidden Maya: A New Understanding of Maya Glyphs. Bear and Company. 1998.

Budge, E.A. Wallis. Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian Texts, Edited with Translations. 1912. Sacred-texts.com.

“Chinese Dragon” at Wikipedia.com, accessed Oct. 1, 2016.

Homer. Hymn to Demeter. Translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White. Loeb Classical Library, 1914. Sacred-texts.com.

Ni, Hua Ching. I Ching: The Book of Changes and the Unchanging Truth. 2nd ed. Hua Ching Ni. Seven Star Communications, Santa Monica CA.

Taylor, Thomas. The Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries: a dissertation. At sacred-texts.com

The Yi King. Sacred Books of the East Vol. 16. The Sacred Books of China, vol. 2 of 6. Part II: The Texts of Confucianism. Translated by James Legge. Web 2015 sacredtexts.com (Note- the first appendix is often attributed to Kung Fu Tzu (Confucius))

“The Trials of the Hero Twins.” Illustration from the Popul Vuh, ca. 1931.