This article is also featured in the October 10, 2025, issue of The Ripple.

Click here to subscribe to this monthly e-newsletter!

Residents of Batavia Township, Ohio have recently petitioned to put two issues on this November’s ballot. One is a referendum to reverse the Board of Trustees approval of a particular planned development in a rural area. The other is an initiative to remove Article 36, which guides Planned Developments (PDs), from local zoning regulations. Both of these efforts are an attempt to curb residential growth.

This township is close to Cincinnati Nature Center, and my goal was to be curious, not judgmental as I investigated the history, purpose, and design of these type of Planned Developments. What I learned is that PDs can be a valuable tool in preserving green space if citizens, developers, and public officials work together for the common good.

Planned Developments (PDs) are permitted when encoded in a municipality’s zoning ordinances. Zoning ordinances and zoning plans are put in place to promote orderly development, ensure compatibility between land uses, protect property values, public health and safety, and preserve the overall quality of life in a community. A zoning plan typically maps out which parcels of land are acceptable for agriculture, business, industry, and different kinds of residential use. There are two ways that land gets developed for housing: through standard zoning or through Planned Developments.

Standard zoning requires a builder to follow strict rules about lot dimensions, building placement and density (number of homes per acre). If developers comply with these zoning regulations, they are pretty much guaranteed to get their plans approved.

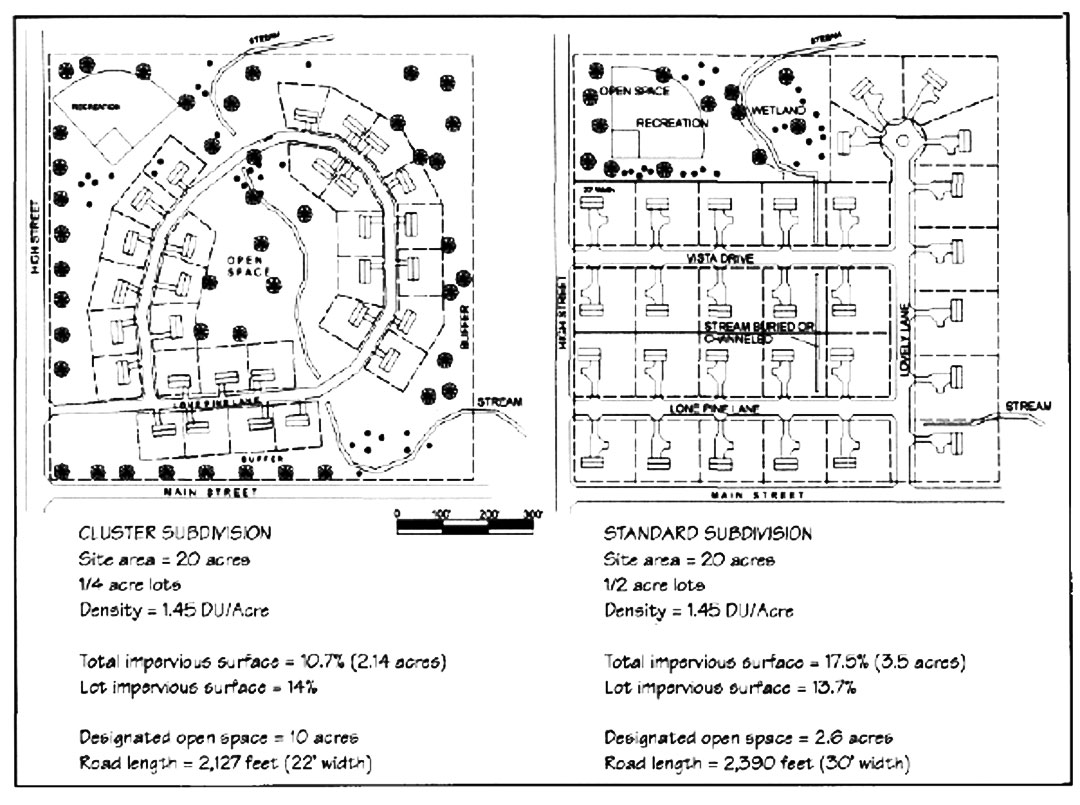

A parcel of land developed with standard zoning sort of looks like a grid of equal portions, with a house in each square of the grid. For illustration purposes, imagine 100 acres divided into quarter acre lots, each with a house. That’s 400 homes evenly spaced on land cleared of trees, then seeded for lawns. No land is set aside to shelter displaced wildlife. No forests or fields remain, except in areas that are too difficult to develop.

But some of the features that give our rural and semi-rural communities their distinctive character can be preserved when subdivisions are designed as a Planned Development. PDs began popping up across the country in the 1950's to promote flexibility and creativity in land use, allowing for a mix of housing types for various needs and budgets, along with a variety of open spaces and community facilities like pools and clubhouses. In PDs, the cost and responsibility to maintain shared amenities falls to residents through their HOA, which is a legal entity.

PDs allow developers to maintain their same return on investment while proposing more flexible designs that can better serve the needs of the community and the environment. They may build in a less land-consumptive way by building fewer homes on larger lots, or they might cluster homes on smaller lots while agreeing not to touch other parts of the land. Conservationists see the potential to preserve agricultural land, green space, and ecologically sensitive areas like wetlands, streams or hillsides with through PDs. The resulting undeveloped portions of the property are permanently protected by the covenants of the HOA.

A conservation-minded community can negotiate with developers to design PDs where the open space of one connects with the open space of others, resulting in large swaths of forests and fields crisscrossing the community. This kind of conservation-based planning is available anywhere that PDs are permitted, if only citizens voice their desire to make it a priority.